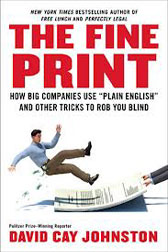

The Fine Print

How Big Companies Use “Plain English” and Other Tricks to Rob You Blind.

By David Cay Johnston. Portfolio/Penguin, 2012.

This article is from Dollars & Sense: Real World Economics, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the November/December 2012 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

Subscribe Now

at a 30% discount.

The new economic reality is that large companies systematically steal from average Americans. Aiding and abetting them are politicians who the companies reward with substantial campaign money and cushy jobs when they retire from politics. These conclusions come from a disturbing and eye-opening new book by David Cay Johnston. The Fine Print possesses the same passion for underdogs and fluid writing style as Johnston's earlier books, Perfectly Legal (2003) and Free Lunch (2007). Its structure is also similar—a set of vignettes or short stories rather than a novel with a main character.

Like all good story collections, a single theme prevails. The preface captures it well. Johnston's mother took him to a baseball game in the 1950s. Imagine, she said, if everyone in the stadium gave you a nickel. Johnston calculated he would have reaped over 1,000 dollars (8,800 in today's dollars). His mother next tried to get Johnston to figure out how to get that nickel.

Each chapter documents one way that big corporations are robbing Americans blind— sometimes by the nickel, sometimes by the hundreds of dollars. Taken together, they portray the systematic plunder of the middle class.

Deregulation, starting in the 1980s, failed to increase competition or reduce fees to consumers. The cost of basic phone service rose 300% from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, and directory assistance calls were removed from standard service packages. Corporate takeovers of municipal services invariably lead to increased rates. The cost of corporate water is around one-third higher than for municipal water. Wielding their monopoly profits, private utilities get laws enacted making it more difficult to buy them out.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission permits pipeline monopolies to charge customers for corporate income taxes that the companies never actually pay to the federal government. We pay $3 billion per year, or $20 per household—around a nickel a day. The firms then pocket this money.

Sallie Mae, the college lender, charges each student $300 to issue a check to his or her school. At a check each semester, the annual cost is $600. Over four years, a student pays $2,400 for a service that costs a few dollars. Such exorbitant fees are standard practice at all financial institutions—for using a competitor's ATM, for getting a copy of a check, and for an overdraft.

It is not only consumers that get robbed. Entergy (a Fortune 500 company) charged the city of New Orleans for bulbs installed at 600 streetlights that did not exist and charged the State of Louisiana for streetlights that were paid for by local governments. The company reimbursed New Orleans $6 million (half of what the auditor said was owed) and then sent the city excessive repair bills the following year.

The somewhat uninspiring book title comes from boilerplate contracts that companies foist on consumers. They allow firms to change terms in the agreement at will; consumers lack equal rights. They also require disputes be resolved through arbitration—where consumers lack many rights and there is no appeals process—unlike the courts. In many instances, arbitrators are picked by corporations; those not supporting big business risk losing future business.

Johnston estimates the annual cost of being nickeled and dimed at $2,400 per family, or around 5% of U.S. median household income. No other country gives corporations such powers to overcharge customers, shortchange workers, bar competition, and buy politicians. At stake is more than money; the very core of our democracy is endangered.

The book ends on a positive note. Johnston suggests eliminating income taxes on regulated utilities, thereby reducing bills for consumers. He wants banks to hold the loans they make, ensuring they make loans likely to be repaid. He wants to end “accelerated depreciation,” the tax deductions which companies can claim based on the supposed depreciation of their assets, which does not increase investment but does cost taxpayers lots of money. And he wants Congress to reverse Citizens United, so large corporations do not have excess political influence.

But most important of all, to keep our pockets from being picked, we have to care. We must speak out against corporate abuse and vote against politicians who enable it. I would take this one step further—go work in political campaigns whenever someone stands up for the people and against the large corporations.

Did you find this article useful? Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.