This article is from Dollars & Sense: Real World Economics, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the March/April 2013 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

Subscribe Now

at a 30% discount.

Beyond Deficit Scare-Mongering

Conservatives’ real aim in their fiscal brinkmanship is to gut Social Security and Medicare.

U.S. politics seems stuck in an endless debate about the size of the federal deficit and federal debt. From congressional Republicans’ refusals to lift the debt ceiling, fears of the “fiscal cliff,” disputes about the “sequestration” and its automatic federal spending cuts, and upcoming debates on a new federal budget and the need for so-called entitlement reform (primarily cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid)—all hinge on the presumed need to get the U.S. budget in balance and curb deficit spending.

In a February appearance on ABC’s “This Week,” Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI), the chair of the House Budget Committee and his party’s vice-presidential nominee in 2012, repeatedly raised fears of an imminent “debt crisis” if the government deficit and debt were not cut quickly and dramatically. “We want economic growth. We want job creation. We want people to go back to work. We want to prevent a debt crisis from hurting those who are the most vulnerable in society,” Ryan argued, “from giving us a European-like economy. In order to do that, you’ve got to get the debt and deficit under control and you’ve got to grow the economy.”

There is no question that the debt and deficit have grown since the economy tumbled in 2008, though the deficit has been shrinking since then and is projected to continue declining as the economy slowly recovers. The federal deficit—the amount by which federal-government spending exceeds federal revenue for a particular year—currently stands at about $1.1 trillion. That amounts to less than 7% of gross domestic product (GDP), the total market-based output of the economy in a year. The federal debt, the total amount that the federal government owes (accumulated over many years of running deficits), is now $16 trillion. That is approximately equal to the United States’ annual GDP. Some of this debt, however, is held by the Federal Reserve and some by federal agencies. When we look at only the debt held by “members of the public” and exclude debt held by the Fed, total federal debt amounts to less than 75% of GDP.

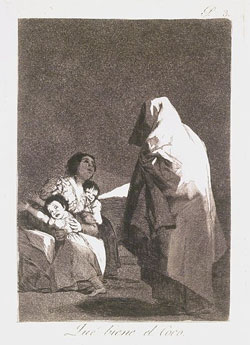

Francisco José de Goya, Que viene el Coco (Here Comes the Bogey-Man), 1799, Brooklyn Museum (Wikimedia Commons).

Is this a sustainable level of federal debt? What is the maximum sustainable level? Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff made headlines in 2010 with research claiming that the debt should not exceed 90% or 100% of GDP, lest it doom future economic growth. That number, however, seems as if it has been pulled out of a hat. The argument appears to be that deficit spending will cause inflation, high interest rates, and a debased currency. But none of that has happened. Since the deficit and debt started rising, the U.S. inflation rate has fallen to 1.3%. U.S. government Treasury bills (short-term borrowing) currently pay interest of less than 0.5%. Since that is lower than the rate of inflation, it means that, in effect, creditors are paying the U.S. government to take their money. Meanwhile, longer-term bonds pay interest of only around 2%. Clearly, investors are happy to hold U.S. government debt, the safest of all financial assets. It is true that the value of the dollar has fallen slightly against the euro, but this is a good thing from the standpoint of a U.S. economic recovery, since it promotes American exports. Recent export growth has been one of the few bright spots in an otherwise grim economic environment.

How Much Can the Government Borrow?

What are the limits on borrowing before it creates economic problems? The answer is that nobody really knows. The Japanese government has a national debt equal to more than twice its GDP, yet is fighting both deflation and an over-valued currency, rather than inflation and a collapsing currency. Interest rates are close to zero. Overall, the country’s economic situation is certainly not good. But by borrowing heavily, Japan has been able to keep its unemployment rate between 4% and 5%, one of the lowest among the industrialized countries. This suggests that the U.S. government could more than double its debt without causing inflation, raising interest rates, or devaluing its currency.

Deficit scolds often claim that households must balance their budgets and limit their debt, and that the government should too. This reasoning is not exclusive to conservative politicians and pundits. Back in 2010, as part of the administration’s pivot away from fiscal stimulus and toward deficit reduction, President Obama said, “At a time when so many families are tightening their belts,” the administration “would make sure that the government continues to tighten its own.” What’s wrong with this idea? First, most U. S. households take on heavy debt. Including credit-card debt, home mortgages, student loans, and auto loans, most American households have debts substantially higher than their incomes. Of course, households can’t continuously take on debt, and must make plans to pay their debt off (or face bankruptcy). That brings us to the second point. Debt taken on by the federal government is unlike household debt, because, unlike households or businesses, the government can print money to pay its debt. (See Marty Wolfson, “Myths of the Deficit,” Dollars & Sense, May/June 2010; John Miller, “Government ‘Living Within Its Means’?” Dollars & Sense, November/December 2011.) People’s willingness to lend to the government reflects the understanding that the U.S. government can always repay debt, as it comes due, by printing money.

Wouldn’t “running the printing press” cause inflation, though? That depends on the overall state of the economy. The Federal Reserve, in recent years, has added nearly $2 trillion dollars to the banking system. Conservative economists and commentators have been long predicting that this would lead to accelerating inflation. Arthur Laffer, a former economic advisor to Ronald Reagan and one of the progenitors of “supply-side” economics, for example, argued back in 2009: “[P]anic-driven monetary policies portend to have even more dire consequences [than large fiscal deficits]. We can expect rapidly rising prices and much, much higher interest rates over the next four or five years, and a concomitant deleterious impact on output and employment not unlike the late 1970s.” Since then, far from the predicted runaway inflation, the inflation rate has tumbled, and currently stands well below the Federal Reserve’s own target rate of 2.0%. When unemployment is high and growth slow, inflation rates fall, almost no matter how much money is added to the economy.

By borrowing money in a recession, the government puts to use resources that would otherwise sit idle in the private sector. Recessions and depressions, after all, are not caused by lack of resources. The labor force still exists, as do all the buildings and equipment that existed before growth slowed. What is lacking is a willingness by private businesses to employ these resources. This is where governments can step in, borrowing funds that would otherwise languish in the banking system, spending them, and putting people to work. Indeed, during hard times, the government should substantially increase its deficit to get the economy back on track. This causes GDP to grow and, as it grows, helps to bring down the ratio of debt to GDP.

Why then is there so much angst and dissent in Congress over federal deficits and debts? Since the Reagan administration, federal deficits have been used by conservatives as a bludgeon to attack social programs and “starve the beast” of government spending. (The phrase, coined by an anonymous aide to Ronald Reagan, has become a conservative mantra.) Under the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, massive tax cuts benefiting primarily the top 1% resulted in massive deficits. The deficits were then decried, as an excuse to demand cuts in federal spending. Since cutting the defense budget is renounced by Democrats and Republicans alike, conservatives demand that social programs be cut instead.

The programs in most immediate danger now are food stamps, the cost of which has more than doubled since the economy tanked in 2008, and unemployment insurance, on which the federal government now spends $110 billion. Also under assault is Medicaid, the health care program for the poor. Spending on all these programs would drop significantly if the government just made concerted efforts to put people back to work.

Social Security and Medicare

But conservatives’ real targets are the two largest non-defense programs—Social Security, which includes not only retirement pensions, but also disability and survivors’ benefits, and Medicare, the health program for the elderly. Yet Social Security and Medicare are financed by payroll taxes and should not even be counted as part of general federal spending.

Social Security is largely a self-financing system. It is funded by a 12.4% dedicated tax on payrolls. This tax is highly regressive. Every dollar in wage and salary income is taxed at 12.4%, up to a maximum of $113,700 dollars in income. Wages above this maximum are not taxed, meaning that lower-income earners pay the full 12.4%, while high earners stop being charged payroll taxes once the maximum is reached. Though half of the payroll tax is formally paid by employers, economists generally concur that workers ultimately pay the whole tax, in the form of lowered wages, according to the Tax Policy Center. Thus, the effective tax rate (total tax paid divided by total income) is 12.4% for those with incomes up to the cap, then falls as one’s income exceeds the cap. Earnings other than wages and salaries—such as dividends, capital gains, and interest, all of which are concentrated among high-income individuals—are not taxed at all.

As a result of the laws setting taxes and benefits, trends in employment and wages, and demographics (current earners who pay the tax relative to current retirees and others who draw benefits), the Social Security system has run surpluses since the early 1980s. These surpluses were then lent to and spent by the United States Treasury and replaced with non-negotiable bonds. The surpluses plus interest accrued by the Social Security Administration on these bonds now add up to a $2.5 trillion trust fund. These bonds, like those issued to any other creditor, represent a promise on the part of the U.S. government to eventually raise revenue (by taxation or otherwise) and pay back this debt.

Why then, if the program has (unlike the rest of the federal budget) produced massive surpluses over the years, is Social Security a target for the “entitlement reform” that conservatives insist upon? For the past two years, benefits paid out by the Social Security Administration have exceeded payroll taxes collected. The difference, a mere $66 billion, has to be made up by the Treasury in the form of actual interest payments owed to the trust fund. In the past, the interest owed by the Treasury on the bonds in the trust fund didn’t entail any cash outlay by the Treasury. These sums were merely credited to the Social Security Administration and added to the trust fund. In effect, the promise implied by the bonds—that the Treasury would someday pay the amount owed to the SSA—was deferred by a further promise (more bonds for the trust fund).

Paying out this interest now seems to be a promise that conservatives have no intent on honoring. To honor these promises would require that general revenue, primarily from the more progressive federal income tax, which mostly hits high earners who have little need for Social Security benefits, would be used to pay benefits to poorer elders—an explicitly redistributive policy which conservatives vehemently oppose. Indeed, the cuts they are now proposing to Social Security benefits exceed the interest needed to meet current benefit obligations, suggesting that conservatives would like to divert funds from the regressive payroll tax to the Treasury (this time, without bonds going into the trust fund in return) to finance other government operations.

The attack on Social Security is bi-partisan, with many Democrats acceding to a cut in benefits by reducing the annual cost-of-living adjustment to benefits in the future. Social Security and Medicare have determined enemies, but they have few principled defenders.

Progressives should be intransigent here: Hands off Social Security. The system is mostly self-financed. For the next 20 years, it will need only a relatively small infusion of cash—cash that it is owed and has been promised—from the Treasury. Lifting the payroll cap and making the tax less regressive would solve most of Social Security Administration’s shortfall. Paying the promises made to Social Security by past Congresses will keep the program solvent until 2035.

Medicare is also financed by a payroll tax, amounting to 2.9% of wages and salaries, with no limit on earnings. As of this year, as a result of the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare), high-income individuals (those above $200,000) will pay an additional 0.9% tax and the tax will be extended to non-wage income. In the past though, the Medicare tax has, like the Social Security tax, also been regressive, since it did not apply to non-wage income. (See John Miller, “The ‘Obamacare’ Tax Hike and Redistribution,” Dollars & Sense, May/June 2010). For years, this regressive tax was levied in excess of what was needed to fund the program, with the balance lent to the Treasury. Medicare has accumulated a trust fund now worth $270 billion. Currently, the benefits being paid out exceed revenues, and Medicare began collecting actual interest (as opposed to interest simply credited to the fund, as in the case of Social Security) a couple of years ago. Soon, it will need to begin dipping into the trust fund itself. As with Social Security, keeping the promises made to Medicare will keep the system solvent through 2024. Containing health care costs would keep the system solvent much further into the future.

So What’s the Solution?

The answer is that we don’t need a solution because there isn’t a problem. There are good reasons to raise taxes on the wealthy and to raise the tax rates on dividends, capital gains, and carried interest, all of which would help close the deficit. Doing so and using the proceeds to fund social programs would go a long way to reducing inequality in the United States. But balancing the federal budget and retiring the debt now—that is, undertaking the same kind of fiscal austerity currently being imposed in Europe—will do the economy more harm than good. The deficit is simply a weapon used by conservatives in the prolonged battle to curb entitlement programs and social supports.

Attacks on entitlement programs and income supports raise a troubling question. Why are conservatives so intent on cutting them? To be sure, there is the general conservative hostility against government spending, and against those they look down on as “dependent” on the government. Entitlements, however, also place a floor under wages and substantially reduce the pain of unemployment. Pulling this floor out from under American workers would almost certainly cause wages to fall precipitously for most working-class people. A cynic might wonder whether this isn’t, after all, the real goal of conservative deficit hawks and their big-business backers.

teaches economics at the University of Massachusetts-Boston and is a Dollars & Sense Associate.

Did you find this article useful? Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.